“Restorative justice is a response to a harmful incident that seeks the inclusion of all involved, in efforts to meaningfully address the harm and restore trust in relationships.” – Just Outcomes

There is a growing movement within the United States to establish an equitable and dignified criminal justice system that aligns with human needs and values. Restorative justice is a budding area of research and practice that offers a compelling framework for this exploration. Juvenile justice agencies are uniquely situated to play a leadership role in the application of restorative justice in America, but accessing this potential requires a considered strategy, an attitude of humility, and plenty of creativity.

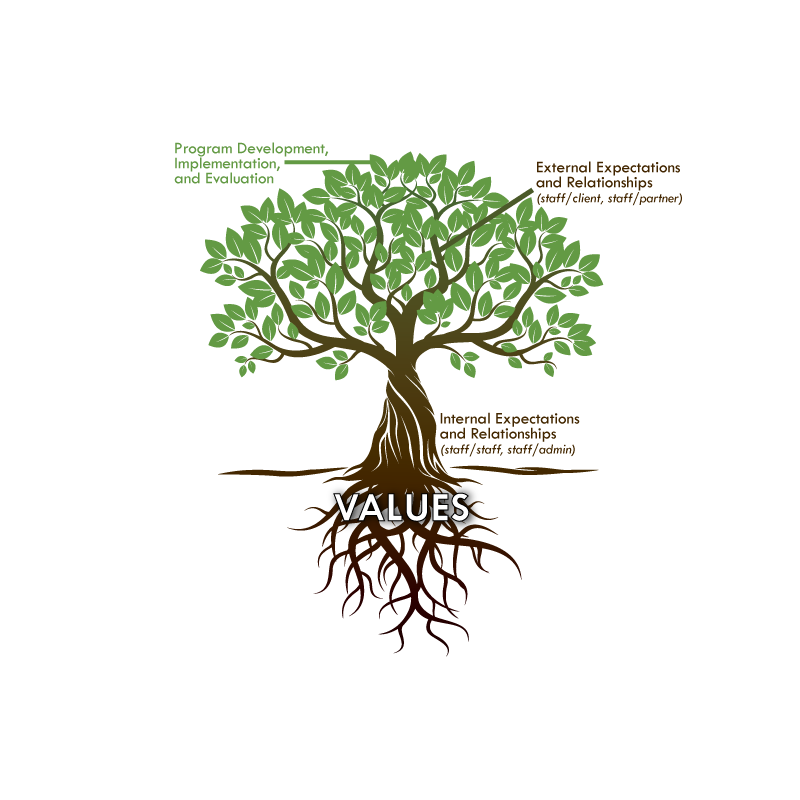

Restorative justice principles can be given expression in programs that convene dialogue and communication among crime victims, people who commit offences, and family or community members. However, these important dialogue programs represent just one aspect of the potential of restorative justice. Accessing the full impact of restorative justice within juvenile justice depends on a holistic view and application of this paradigm. In our work with juvenile justice organizations, we have adopted the common metaphor of a “tree” to represent this broader vision. Most lasting and successful change processes within Juvenile Justice include simultaneous or consecutive efforts at various levels, which we describe here as the tree’s roots, trunk, branches and leaves.

The Roots: Restorative Justice Values

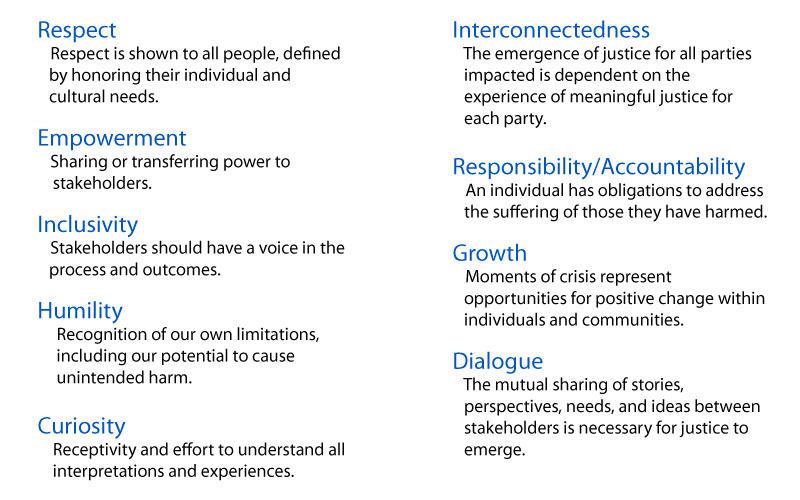

“Restorative justice” terminology emerged as recently as the 1990s (see Howard Zehr’s 1990 book Changing Lenses: A New Paradigm for Crime and Justice). However, even its early advocates understood that this paradigm was really a newer expression of timeless ideas present in indigenous and faith-based value systems. Restorative justice signals a return to what many of us would already articulate as among our own core values: the importance of treating others with respect and dignity, taking responsibility for our actions (or inactions), striving for the healing of emotional wounds, and listening even to those with whom we differ, for example. Following are frequently cited values underpinning the work of restorative justice.

Juvenile justice agencies move towards restorative justice when such values are given voice and expression, both in the workplace and in the communities they serve. On one hand, the shift toward more explicit alignment with these values is an inviting and invigorating processes of change. On the other hand, change always comes with a certain amount of struggle.

In the case of juvenile justice services or any other agency with designated authority, a fundamental implication of authentic steps toward restorative justice is the re-examining of power.

This shift demands that the agency and its individual personnel consciously and critically reflect on their use of authority, identify hidden assumptions and power dynamics driving leadership and staff behaviors and critically examine their communication styles. If power and authority remain unconscious, attempts to integrate restorative justice values may become co-opted into existing norms, even resulting in unintended harmful outcomes for the clients served.

The Trunk: Internal Expectations and Relationships

What is it like coming to work in the morning? What is the tone of working relationships among your agency or department’s staff, and what processes take shape when those relationships break down? The answers to these questions often have a stronger effect on service delivery than we might assume.

Making changes in individual and organizational practice requires some risk. A staff culture based upon mutual respect, trust and inclusion allows us to push toward the limits of our capacity and creativity while feeling supported and encouraged. Working in isolation, worrying about the judgement of others, feeling ashamed or disconnected are (all too common) detractors from innovation.

Characteristics of a strong “trunk,” (i.e. internal processes conducive to a shift toward restorative justice implementation), include:

- frequent opportunities for staff community-building and relational awareness beyond one another’s “role;”

- modeling and communication of restorative justice values from all leadership;

- robust organizational conflict resolution processes; and,

- workplace discipline and grievance processes that are congruent with restorative justice values and principles.

- working to encourage the long-term retention of personnel;

One example of a practice that can help to foster a strong “trunk” is to make simple adjustments to the way that staff/team meetings are conducted. What if these meetings were a time for honest and transparent communication among staff, both personally and professionally? A simple and adaptable facilitation tool, emerging from the indigenous roots of the restorative justice field, is the use of “talking circles.” For a highly accessible introduction to this methodology, we recommend Kay Pranis’ The Little Book of Circle Processes.

The Branches: External Expectations and Relationships

This level of implementation refers to your agency’s existing interface with clients, community partners, or the public. These relationships can be profoundly strengthened – with lasting results on the outcomes of justice – when Juvenile Justice professionals draw upon the principles of restorative justice. Some examples include:

- seek the involvement of your youth clients in the decisions affecting their lives;

- reach out to crime victims in order to understand and address their needs to the extent possible;

- foster youth accountability toward their victim(s), as opposed to mainly toward the justice system;

- develop a language of engagement toward clients that builds empathy and intrinsic motivation rather than eliciting shame and the fear of punishment;

- involve the client’s extended family/support networks in decision-making;

- reach out to community partners to involve them in agency initiatives and service delivery; and,

- use your agency’s reach and networks to identify gaps in service delivery, and work towards more resilient and equitable communities.

The Leaves: Program Development, Implementation, and Evaluation

The most visible level of restorative justice implementation is the creation of new programs designed explicitly to facilitate dialogue and communication between youth, crime victims and their communities of care. There are various models of restorative justice dialogue (victim-offender dialogue, peacemaking circles and conferencing are among the most common), each of which brings its own unique strengths. Those implementing facilitated dialogue programs within juvenile justice are encouraged to:

- partner with community-based nonprofit agencies for program delivery to minimize risks of co-optation and maximize efficiencies;

- ensure that all cases include careful case-preparation and follow up in addition to various options for interpersonal dialogue; and,

- include monitoring and evaluation expectations within any program contract to ensure service integrity.

For some juvenile justice agencies, restorative justice is put into practice through new programs aimed at enhancing services for a specific stakeholder group or one aspect of justice. Examples of these restorative justice-informed programs include:

- Victim impact programs aimed at pro-active outreach to crime victims to explore impact, needs, and level of involvement they would like to have in the juvenile justice process;

- Restorative community service programs aimed at using community work service as an opportunity for meaningful accountability/amends while enhancing practical links and relationships between youth and community members; and,

- Restitution programs aimed at supporting young people to follow through with their financial obligations to victims through meaningful work contracts in the community, and keeping victims informed throughout the process.

A fundamental principle of quality restorative justice practice is to design programs in such a way as to be maximally flexible and responsive to the individuals and communities they are intended to serve.

Five Priority Strategies for Implementation

Keeping in mind the “tree” metaphor for holistic restorative justice implementation, here are five primary considerations for moving forward.

- Change How Power is Wielded: Re-examine the use of power and authority in organizational hierarchies, with clients and families, and with community partners – aim towards power-with others, rather than power-over others.

- Strengthen the Trunk: Start restorative justice implementation internally through attention to organizational culture, relationships, conflict and grievance policies and procedures.

- Strengthen Service to Victims: Strengthen service to victim/survivors through program development, attentive youth case management, and collaboration with victim services/advocates. Consider convening and maintaining a crime victim advisory committee.

- Actively Engage Community: Reach out, listen to, educate, and empower community members and organizations as primary partners in the administration of justice.

- Reallocate Funding: Costs are always a factor in decisions about organizational change. While finding new sources of outside revenue may be necessary for some restorative justice initiatives, try re-allocating funding within your existing budget to align with restorative justice priorities.

Above all, the shift toward a restorative vision for your agency or department may begin with you. In the simplest form, this shift is characterized by a willingness and commitment to view all aspects of one’s work – whether with co-workers, partners, clients, victims or other stakeholders – through a lens of respect and right relationships.