Whether in our roles as parents, co-workers, employees, or teachers, many of us are affected by bullying behavior. How do we, as bystanders and supporters, be of help in these situations – and might we set the conditions in motion that make bullying less likely in the first place?

Last week, I was at the playground supervising my daughter when a group of kids tumbled in front of me, two of them seeming to be taking down a third. My initial perception was that they were all smiling and giggling. But. The third kid was held down by the two others (a girl and a boy) a bit longer, and then had his head grabbed at. They all seemed to be laughing, but I stepped forward, monitoring the situation, most likely a big frown on my face. I may have analyzed too long, as another parent stepped in and said unequivocally, “Hey, not cool, let that kid up!” They immediately did so, and all of them ran off playing.

What had happened? I was inspired by the decisive parent and wondered if I had indeed just stood by watching as bullying happened in front of my face. I spend time at this playground just about every day, and have come to trust the community connection amongst the kids and the families at this place. How is one to know when bullying—as opposed to rough play– is taking place, and how does one best intervene?

Well, rough play is certainly one thing and I think most adults know there’s a duty to intervene immediately when it gets too rough (some of us slower on the draw than others!) But then we also need to consider other bad behaviours, and how to appropriately intervene: rudeness, meanness and bullying. It’s important to understand this when dealing with children, and there’s definitely implications for our adult interactions too. An article written a few years ago now by Signe Whiston makes the following distinctions:

Rude = Inadvertently saying or doing something that hurts someone else.

Mean = Purposefully saying or doing something to hurt someone once (or maybe twice).

Bullying = Intentionally aggressive behavior, repeated over time, that involves an imbalance of power.

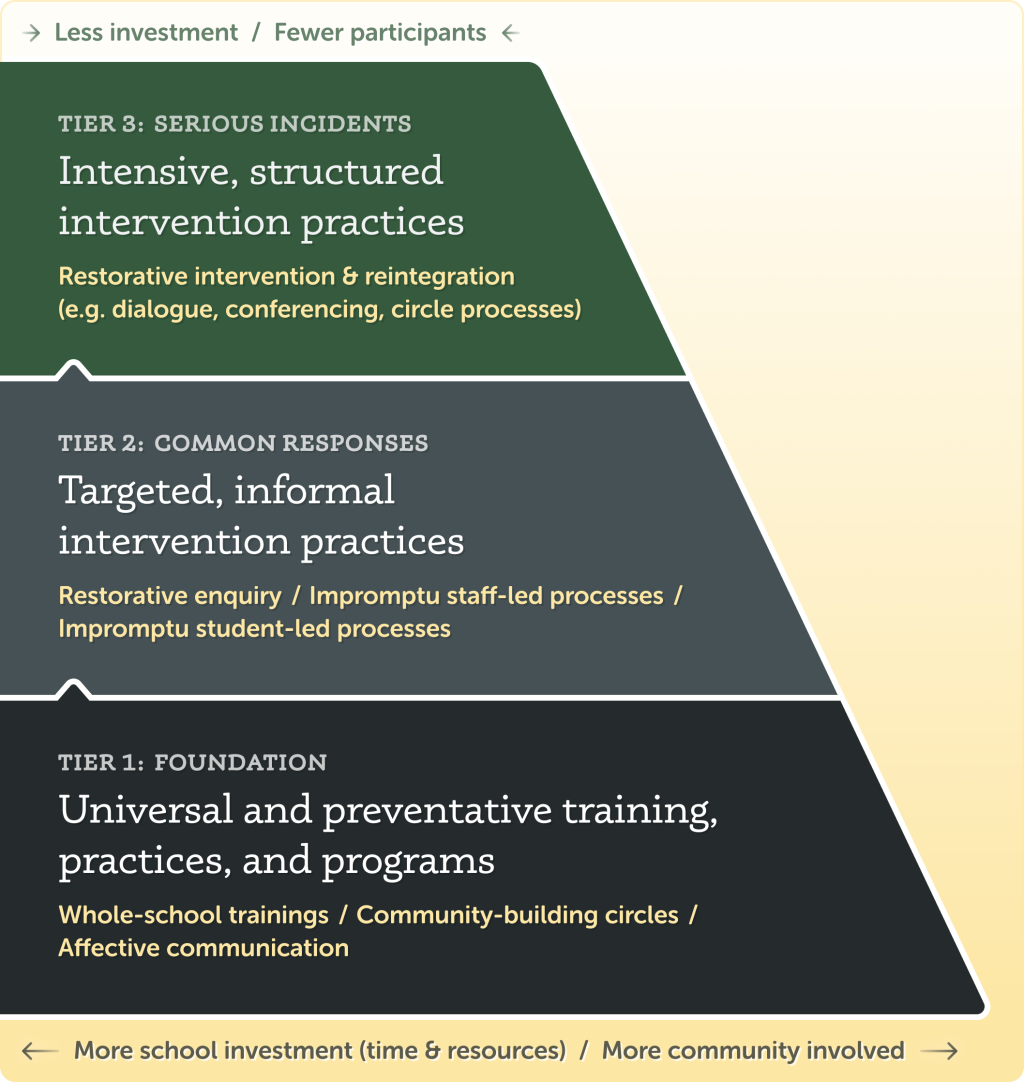

Spoiler alert: I’m not able to provide all the answers to how to deal with each of these behaviours. But understanding these distinctions relates to many contexts (playgrounds included!) A framework developed for restorative justice implementation in schools is useful here – a “Tiered” approach (pictured below) to building a restorative culture. So, to apply it here, in Tier 1 we are laying foundations for good relationships to happen, with no outside interventions required. Things like encouraging inclusive interactions, educating ourselves about any privilege or power we may hold, and being kind to one another. Individuals are relationally responsive and connected at a level that disagreements, misperceptions, misunderstandings, etc. do not elevate to the level of needing someone else to intervene. Rudeness may happen, but those involved are able to navigate these moments in ways where disconnection does not occur.

At Tier 2, we start to respond to negative behaviours such as rudeness/roughness and meanness, and at Tier 3 we address the least common (but most devastating and very real) category: bullying. We need to tailor our actions and interventions accordingly in order to build restorative culture where connection is built and harmful behaviours are dealt with appropriately. Allow me to explain using this pyramid graphic:

In Tier 1, a large portion of what we deal with in our lives is in this foundational category, and it has to do with the kind of culture we build in any kind of community (school, workplace, neighbourhood, etc.). Usually when I’m at the playground in my neighbourhood, I feel like many/most adults are working on supporting healthy, connective culture at Tier 1, before any intervention is even required. It requires champions, commitment and vision to allow this kind of connection-based culture to flourish. Tier 1 involves teaching boundary skills so that the youth on the bottom of the pile, if feeling at any point uncomfortable or unsafe can state their need for the others to stop, and teaching empathy and responsibility skills/attitudes so that the two youth on top can respond to the request to stop with empathy, and take responsibility for the impact they had even when it may not have been intentional. Many of these attributes of human communication are central to restorative justice philosophy. And it will directly influence how well things go in Tiers 2 and 3.

So, let’s now focus on Tiers 2 and 3, which require intervention. Dealing with rudeness requires intervention, but may need just a few simple statements. With kids, we might say: “Actually, that was rude/too rough. Please find another way to say that/Please find something else to do.” With our fellow adults, we might say: “Hey, I’m not sure you realize how that landed, but it was pretty harsh! Is there something more I need to know about ____?” Dealing with meanness will likely require an even more targeted intervention. With kids we might invite a few kids into an informal conversation: “Emma, Jody, Sophie—could you come here for a second? I noticed Sophie crying by the fence for a second time this week after something happened with you guys, Emma and Jody. Can we talk about how you’re doing, Sophie, and find out what we can do next to make things better?” With fellow adults, the gist is the same if you are dealing with someone being mean. It most likely begins with the sentence: “Can I talk to you in private for a bit? Do you have some time right now?” and then describing as objectively as possible what happened that was offensive/mean and launching into a problem-solving conversation.

Dealing with bullying and other major offenses in Tier 3 is serious and intensive intervention is required. With kids and adults, we will likely need to do a great deal of individual check-ins and assessments, and possibly involve parents, and/or authorities, and/or other affected persons. We need to take time to ensure the person being harmed is ok and what they might need to feel safe. We need to spend time talking with those perpetuating harm and find out how they are able to take responsibility and be accountable. We may need to assess power imbalances, and determine whether identity, race, gender, sexual orientation or other factors are playing a role in the intention and/or impact. When appropriate, we may undertake a safely facilitated dialogue processes with affected parties and their communities to determine how to address the harm and move forward. Many call this type of approach “restorative justice” or “restorative practices”. This approach will be most effective in environments where consistent responses to rudeness and meanness in Tier 2 are frequently practiced, accepted, and well understood—and well supported within Tier 1.

The parent at the beginning of this blogpost intervened swiftly and informally, which belongs in Tier 2. Perhaps that parent had a lot of experience building the kind of culture she wants to see in Tier 1. Accordingly, those kids can usually expect that a community culture is being built on that playground that such behaviour will not be ignored, so we will be less likely to see Tier 2 and 3 stuff going on. If we were to witness the same behaviour at the playground over time that started to reflect a power imbalance, we’d start to figure out how we might need to initiate Tier 3 interventions (restorative justice) while also thinking about how to build our communities (Tier 1) and strengthen our responses (Tier 2).

The 3-tier pyramid model applies to many different contexts and forms the basis of restorative culture change. Bullying will emerge in cultures or sub-cultures that tolerate it, and is unlikely to flourish in environments actively supporting a restorative culture. We invite you to think about how this 3-tier thinking might apply to your context, and how you can gain the mindset and skills to address destructive behaviour at every level, from the playground to your workplace.